Taller people tend to be happier than shorter people, members of racial/ethnic group X prefer dating members of group Y more than group X, children who don’t eat breakfast in the morning receive lower grades. The list goes on… It really does. You can find it here.

Every day a new ‘study’ comes out claiming how ____ is associated with ____. Despite the provenance of these studies, the effect is the same: we are left with a feeling of despondency, and feel increasingly helpless. Our lives seem to be controlled by dark, powerful, and often sinister external forces, beyond our comprehension, as divined by the scientific priesthood. When queried, this priesthood buries the questioning neophyte with incantations of p-values, probability mass functions, and Bernoulli trials. I’ve met numerous people who have blamed their lack of success in dating, life and their workplace to some abstruse research that they read online:

- “Man, I didn’t get that job because I wore a red tie rather than a blue one; a study I read last weekend show that wearing a red tie to an interview is less likely to get you a job”

- “She didn’t go out with me because I was too dark, too tall, too short, from ethnicity/racial group X, etc; Come on, you know how, statistically, ___ is a significant factor influencing second date outcomes among college students.”

- “I didn’t do well on that test because my parents live in a two bedroom house, rather than a three bedroom house. Studies show that…”

Sometimes, the despondency created is so profound that entire brotherhoods are created, based on a shared bonding over some ‘scientifically supported’ disadvantage. As they say, misery loves company…

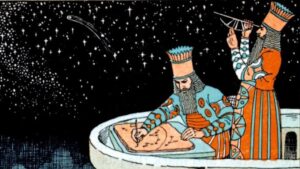

The ancients looked up at the night sky and ascertained that the trajectories of the stars determined the trajectories of their lives. Today, such a person would likely be called a little superstitious. But, if you replace the talk of stars with that of correlations, then you are automatically labelled “scientifically literate, wise, and up-to-date with the latest research.”

Though (respectable) dinner table conversation has shifted from talk of black cats, supernatural spirits, and constellations to p-values, Pearson’s correlations, and null hypotheses, the effect on the individual is the same as it was a thousand years ago: a crushing sense that one’s life outcomes are determined by powerful, mysterious forces from which there is neither reprieve nor escape.

Surprisingly, the solution to this puzzle comes from those great personalities of the COVID-19 pandemic: those who refuse to wear a mask. Ironically, despite their distrust of the scientific establishment, they embody the greatest ideal of science: skepticism. As Yuval Noah Harari notes in Sapiens: A Brief History of Mankind, the embodiment of modern science is the Latin “ignoramus” (literally “we do not know”). According to Harari, man first began to acquire unprecedented powers when he first admitted its ignorance. Indeed, from my inferential statistics class in graduate school, I recall my professor describing the importance of taking the null hypothesis (scientific speak for the prima facie/base case), to be the opposite of what one was trying to show. For example, if one is trying to show that men are on average taller than women, then one must initially assume that men and women have the same height. Skepticism from a scientist is akin to due diligence by a banker before giving out a loan: a necessary and required step in the process. Incidentally, I recall that the students who were the most entertaining to have in class were also those that were the most skeptical. They challenged the professor’s ideas, and in the process turned a lecture into a lively dialogue. They also invariably scored the highest grades. And it is this skepticism that will cure our despondency…

Take the case of online dating. The narrative is that members of “Group X tend to prefer members of group Y more than Group Z, as evidenced by higher swipe rates and response rate to messages”. By the way, this is a real study. As is to be expected, members of group Z do not take kindly to this discrimination. The Achilles Heel of such studies lies in their setup:

Such studies are mainly observational in nature. In other words, they observe some dependent variable (in this case match/response rate) and some independent variable(s) (in this case race/ethnicity) and then draw conclusions. The trouble is that anything can possibly go wrong in between.

Aha, skepticism to the rescue! There are indeed a thousand and one things that can go wrong with these types of correlational studies. A non-exhaustive list is provided below (an exhaustive list can be found here):

- Mere exposure effect: It is well-known that people tend to develop a positive impression of things that they are continually exposed to. What if members of Z are in the minority on the dating app? Indeed, then they are likely to not be selected simply due to the mere exposure effect.

- Selection Bias: What if the people who tend to join this dating app tend to be systematically different from members of group X overall in the population? For example, what if members of group Z on the dating app tend to be shorter/taller/richer/more shy/more outgoing than members of group Z in the wider population? Another hypothetical example, would be sampling people from LinkedIn and using that as a means to estimate the national average income. Such an approach would miss out on blue collar workers and other low-skilled labor that do not normally use LinkedIn.

- Limitations of scope: The conclusions drawn from such as observational study are limited to the digital world of online dating, and critically not the real-world. It might be questionable to extend its findings to the real-world realm where people get a more complete window into a potential partner’s life before making a decision as opposed to the customary 5 photos, and a (hopefully) witty tagline.

These insights are not an exclusive discovery of mine. The researchers themselves recognize them too. If you’ve ever wondered why researchers in the social sciences often use circuitous language like “tends to”, “associated with”, “likely to”, etc. instead of the simple “because”, then this is why. Indeed, sometimes researchers sound a lot like mutual fund advertisers on TV with their lightning fast, non-committal, seemingly disingenuous spiels on how “investments are subject to market risk, …”

By now, you might’ve recognized that science is not the infallible edifice that the general public makes it out to be. Scientific conclusions should not be accepted carte blanche, but rather be received with the skepticism that was incipient to their genesis. It is a veritable tragedy that many people continue to use such fatalistic “science” to limit the possibilities in their lives. Sadly, such people ignore the infinite subjectivity that make us so human in favor of a rigid, rules-based worldview that is a prison of their own making (with some ideological assistance from science)…

Perhaps, a good (and more difficult) topic for future study would be how many short people concluded that they would live unhappy lives, children who convinced themselves that the reason for their academic shortcomings lay in their breakfast-less mornings, and young adults who failed to realize their inner romantic, all due to a poorly understood science.