I’d like to begin with a series of interesting observations:

- During my recent foray into grad school, I encountered a girl who was a vociferous proponent of multiculturalism and diversity, yet surrounded herself with a (mostly) homogenous friend circle similar to herself, while making little effort to get to know the cohort’s international student community.

- Another student, a clamorous proponent of democratic rights and values, jumped at a Facebook data scientist job offer, a company which is (rumored) to pay handsomely, but is also (rumored) to have played a central role in the 2016 Cambridge Analytica affair among another anti-democratic activities.

- A vocal cabal of residents at Berkeley’s most ridiculously expensive dormitory, truly an edifice of capitalism and its twin inequality, became fervent supporters of socialism/communism enough to make Che Guevara blush in embarrassment.

- All of today’s tech companies have a singular goal: “to make the world a better place”. Yet, most operate as uncontested monopolies, are quick to crush competition, concentrate unprecedented wealth in an ever smaller corner of the economy, and spend millions on lobbying pliant government officials. In other words, they are as fierce and ruthless as any business organization of the past, yet have been effectively able to don the cape of goodness. How?

- Another family friend, who earned her academic laurels in the august fields of poverty studies and women’s studies, employs a low-cost maid from the other side of the world, whom she visibly treats horribly.

My intention in sharing the above is not to indict but to illustrate. What explains these seemingly paradoxical observations? The Allure of the Abstract. Simply put, lending one’s support to ideas in the abstract will always be easier than contending with them on an individual, person-to-person level.

The Allure of the Abstract at work: Every one of humanity’s great -isms (socialism, capitalism, communism, nationalism, …) began with noble aims (in the abstract). Many strove to make the world a ‘better’ place. How these ideas eventually turned out for the every day people who experienced them, is a different story. Many led to violent state repression, genocide, and apocalyptic wars.

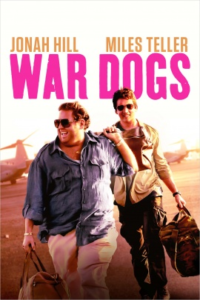

As Jonah Hill’s character, who plays an unscrupulous arms dealer bro in the dark comedy film War Dogs (2016), shrewdly notes “All the money is made between the lines.”

But I surmise that the allure of the abstract goes beyond the realm of the latest social causes: it might explain the popularity of sports teams. In fact, the stories I mentioned above bear strong parallels to modern sports teams:

- When you support, say Manchester United, it does not necessarily mean that you will get along with each of the 11 Red Devils. The statement of ‘support’ is being made in the abstract, not at the individual level.

- However, you nonetheless get to make a bold statement of your fervent support to the world. For example, this can be done by wearing the team’s bright red colors, posting on social media, donning hats, putting stickers on your car, signs in your yard, and being knowledgeable about the latest transfer to FC Barcelona.

- As a result, you also get access to a ready-made community of fellow supporters globally, with whom you share ideology, and a shared distrust of Manchester City.

- You can easily support teams from other sports with no ‘conflict of interest’ arising . For example, it is perfectly acceptable for a Manchester United fan to be also supporter of Seattle Seahawks, the LA Lakers, or whatever sports team catches your fancy — as long as its not in the same ‘sports universe’.

- Due to its abstractness, you can easily moderate the level of investment into the supporter relationship based on your convenience. Big exam or work deadline coming up? You can simply ‘pause’ your support for the team (not easily done for some) and then ‘restart’ when convenient. Doing the same is considerable different (and frowned upon) in the individualized realm of human relationships.

- Critically, corporations can indicate support for the Manchester United abstraction by paying a sum of money and getting their name prominently featured on the team jersey. In other words, companies can create customer brand awareness and the concomitant revenue boost simply by purchasing space on the “Man Utd” jersey.

In other words, you get to “support” Manchester United, without ever having to contend with the uncomfortable possibility that you may not actually get along with any of their players, for example, at the extremely individual level of a roommate. Up till here, there’s nothing amiss (apart from a few accusations of hypocrisy here and there — itself a nebulous concept). Yet, things can quickly go awry in one key way:

What if we, as a society, were to start using support of a certain sports team to indicate moral goodness to the exclusion of all others?

For example, supporters of Liverpool are declared to be more ‘morally upright’ than the supporters of all other soccer teams and non-supporters as well. This is problematic because of the deductive logic it entails: support (or lack of support) for an abstract cause is used to draw a conclusion about the goodness of an individual, while completely ignoring the individuality of each human being. Such deductive logic has been at the heart of history’s most devastating ethnic conflicts and human tragedies. Are we heading in this direction as a society?

Given the pernicious effects of the Allure of the Abstract, I would venture to say that a fairer way to judge a person’s ‘goodness’ is the old-fashioned way: at the individual level.

A lifetime of good actions, rather than adherence to an abstract cause, might be a fairer way to judge a person’s goodness.